Picture is from Hope Hilton,

"Wild Bill" Hickman and the

Mormon Frontier, p.153.

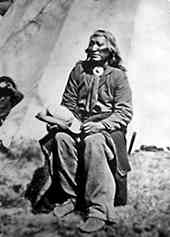

Chief Washakie of the

Shoshone Indians

Brigham Young was the first Territorial Governor of Utah. He also held a federal appointment as Indian Agent for the territory. The Indians were rapidly being displaced by white settlers, and mediating the inevitable cultural conflicts was no easy task. Brigham counseled with Indian leaders in person whenever possible, but other dealings were done using special messengers, who spoke the Indian language and whom the Indians trusted.

One of these men was our Bill Hickman. The following article by a BYU historian provides some information on this interesting part of Bill's career and his dealings with the Indians on Brigham's behalf prior to the Utah War:

Brigham Young-Chief Washakie

Indian Farm Negotiations,

1854-1857

Edited by

RHETT S. JAMES

Very early in the Mormon Utah experience, the need for the development of a workable Indian policy arose. Mormon leader Brigham Young recognized that in order to found the hoped for desert kingdom in Utah Territory, peaceful relations would need to be secured with Indians of the region. This was not only because Indian hostilities could endanger Mormon economic development, but because Mormon scripture stipulated that such a kingdom could not be fully established without gathering a remnant of the Indian population into Mormondom.[1] The Mormon Indian farm program became the principle means of achieving this end. Young felt convinced that only when the Indians had attained a respectable degree of economic self-sufficiency would peaceful relations exist between the two peoples. In his attempts to implement the Indian farm program, Young came into contact with the Shoshone Indians and their best known of chiefs--Washakie of Wind River, Wyoming fame. These contacts proved to be among the first which resulted in the only significant success experienced by Young and his successors in the Indian farming efforts. of the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries.[2] The following letters found among the papers of Brigham Young mark the known beginning of negotiations between Young and Washakie on the matter of Indian farming.[3]

I

BRIGHAM YOUNG, SUPT. OF INDIAN AFFAIRS,[4] TO

WASHAKIE AND TATOWATS, SHOSHONE CHIEFS,

DATED GREAT SALT LAKE CITY, JUNE 28, 1854[5]

To Wash-e-kik and Tatowats,

I write to you because you was not afraid and came and see me, so I am acquainted with you I would like to be acquainted with all your people.[6] I love you very much and have always loved you. I know that you are the very best Indians in all the mountains, and I know that you have always been friendly to us. We want to do you good and always be good friends and if you will be friends with us we will live together, and always be good friends. Tis true that we wish to cultivate some of your land and raise grain and vegetables if they will grow there and we expect to furnish plenty of trade so soon as we can obtain it to trade with all the Shoshones. James Bridger violated and broke the laws and probably would have been fined if he had not have fled, but his best plan would have been not to have broken the laws in the first place and in the second place not have fled or resisted the officers but stood his track, perhaps he might have got clear and not even been fined. He was accused by the emigrants of furnishing the Utah with ammunition to kill the whites with: If we find that we can raise grain etc. on your land we will buy as much of it as we want to use and you can still live about them so you do not destroy the grain or do damages. We would be glad to have you always with us and help us raise grain and we would teach your children to read and write. We do not wish to injure you or infringe upon your rights in the least but to do you good, neither do we injure the Mountaineers but they are white men and must not break the laws if they do they have to be punished.[7] I would be glad if you and <p.247> the other Shoshones and chiefs would come to the city so that I could get acquainted with them also. I want you to show this letter to the other chiefs. We send you some trade, all we can at present, but will send more when we can obtain it.[8] You and us have always been friendly why should we not remain so? Anybody who seeks to make difficulty between us does wrong; they ought not make difficulty between you and us because they themselves have got into difficulty and have done wrong. Let them do right as well as you have done and then all would be well.

<p.248>

O. P. Rockwell,[9] Amos Neff,[10] and Geo. Bean [11] will take out some trade and talk with you and I hope transact business to your satisfaction. I would like to meet you at Green River or Fort Supply[12] but the water is too high for me to come so soon. I intend going there this summer when I would be glad to meet you and the other Shoshone chiefs. If any man tell you or Tatowats that we are going to kill off the Indians or would do it if they should come against us, you just tell them that they lie for we are your friends and brethren and not your enemies and if we live friendly with each other and do each other all the good that we can the Great Spirit will be pleased with us and make us happy.

I am your friend & Brother

Brigham Young

II

BRIGHAM YOUNG, SUPT. OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, TO

CHIEF WASHAKIE, DATED GREAT SALT LAKE CITY,

AUGUST 15, 1854

To Wash-e-kik

I write this letter to you, and send it to you by Mr. Ryan,[13] who will explain the same to you.

We are glad that you are coming to see us, and think that you had better come about the 4th of September, when the moon will be full, to give good light. I think we shall meet you at Parleys Park, [14] where we can find plenty of grass for your horses, and stay over night. We will then come into the city with you, and as many <p.249> of your principal men, as wants to come. But the main camp, had better stay at that point, on account of feed for horses, as it is extremely poor about the city.[15]

We shall make you very welcome, and be glad to see you, and do the best that we can for you while you stay. Mr. Ryan says that he thinks it will suit you to come about that time, and think it will be better to meet you there, than for you to bring all your horses here, where the grass is all gone.

We will bring you some beef cattle, and corn if we can get it, but the grasshoppers have destroyed our corn. We shall bring you some flour, so that you may have something to eat, while you visit with us.

I expect from what I hear, to see a great many of your nation this time, and hope I shall, as I love the Shoshones very much. They have always been good and friendly to us, and we think a great deal of them. When I see you, I can talk better with you than I can write.

I am your friend & Brother,

Brigham Young

III

BRIGHAM YOUNG, SUPT. OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, TO

CHIEF WASHAKIE, DATED GREAT SALT LAKE CITY,

NOVEMBER 6, 1854

To Wash-e-kik

I send this my letter to you by your good friends Mr. Ryan and Mr. Hickman.[16]

I was sorry to learn that your people are so disposed to break up and scatter about.

I love the Shoshones, and therefore wish to tell you and your people some of my ideas which I think will be for your good. I think it is a poor plan for the Shoshone to scatter so much, and <p.250> roam about in such small parties. This plan exposes you more to the attacks of your enemies.[17] I also think it unwise for you to depend entirely upon hunting and fishing for living, for game is often scarce, and often hard to be caught, and in such cases you suffer from hunger, and sometimes starve. . Now I would like to see your people collect into large bands, and begin to cultivate the earth that you may not starve, when you are unfortunate in hunting. You have many good plains that you can settle upon to raise grain & vegetables. Mr. Ryan tells me that a lace in Green River called "Brown's Hole" is a good spot for raising what corn, potatoes, pumpkins, and many other things which are good to eat in the long winter, without being obliged to hunt in the cold. I will send good men of my people to help you make farms, and help and show you how to raise grain. I hope you will see that this is for your good, and conclude to begin to till the earth next spring and I will help you to seek tools, and such aid [as] you may wish to give you a start. During the coming winter I think it would be a good plan for you to go to some good hunting grounds, not in too small parties, and lay up plenty of meat, [18] and dress skins, and robes and next spring I will send men with blankets, powder, lead, beads, and such trade as you may wish, which you can purchase with your robes, skins and such articles as you may have to exchange.

I hope you will understand that I am your friend, and brother, and that I desire to do you all the good I can. I also wish you to understand that Mr. Ryan, Mr. Hickman and Mr. Brown, [19] and such of my friends and brothers as I may send you, are your friends and brothers and wish to do you good, and presume your hearts will be good towards them and that you will use them well, and open your ears to their good council.

Now, Wash-e-kik and the Shoshones I want you to remember these my words to you and open your ears well to understand them, and do not forget that I am

Your friend & Brother

Brigham Young

<p.251>

IV

BRIGHAM YOUNG, SUPT. OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, TO

CHIEF WASHAKIE, DATED GREAT SALT LAKE CITY,

MAY 1, 1855 (Extracts)[20]

Now we have come here into these vallies of the mountains, just at the right time to do good if you will harken to our instructions. The Lord directed us to come here and when you got well acquainted with us and our people, you will understand why. Now, you pray to the Lord and ask him to open your eyes so that you can see and understand about us, and see if he don't manifest to you that what I tell you is true.[21] We can learn you how to get a good living. If you will do as we tell you--and that is to plant and sow grain, and take care of it when it ripens, and raise stock and not ramble about so much, but make farms and cultivate them. We will not disturb you when you make farms and settle down but now no matter where we settle you feel that it is an infringement upon your rights [22] but it is not so, the land is the Lord's and so are the cattle and so is the game; and it is for us to take that course which is the best to obtain what he has provided for our support upon the earth, now we raise grain and stock to last us year after year, and work to do so, but you depend upon hunting wild game for your support, that was all right when you had plenty of game, and it was to your own country, and you did not have to go so far away off into the Sious and Pawnees Country after it, and before the Lord sent us to do you good, but now you see it is different, and you should make locations on good land and raise grain and stock and live in houses and quit rambling about so much? [23] The <p.252> Creek and Cherokees have done so long ago and now many of them are very rich, have good comfortable houses and plenty of property [24]. If you do so the Lord will be pleased with and bless you which I desire with all my heart. My heart is good towards you and your people and I wish to do you good and so do my brethren. We want you to be our brethren also. Bad men will give you whiskeys and when you drink it, it makes you mad, you must not do so, it is always bad for Indians to drink whiskey it kills them off. You ask the Lord to tell you if this is not so. I am well pleased with you for you have always been friendly and good so far as I know and I hope that you will continue to be so.

V

BRIGHAM YOUNG, SUPT. OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, TO

CHIEF WASHAKIE, DATED GREAT SALT LAKE CITY,

AUGUST 11, 1856 (Extracts )[25]

Wash-e-kik Chief of the Shoshones

I send out by Brother W. A. Hickman a few presents which I trust will be satisfactory to you. I have heard a good report from you and your tribe, and am glad to hear of your friendly feeling towards the whites, and that you are willing to have them settle on <p.253> your land and raise grain,[26] I am your brother and want to do you good. I want to have all the Indians live at peace with each other and be at peace with the whites. I have thought a great deal about you and have seen that you have a great deal of difficulty to support yourself and tribe--you have to go and hunt Buffalo to get a living, this brings you into collision with other Indians who are perhaps hostile and exposes you to danger.

Moreover the game is continually getting scarce, which makes it more and more difficult for you to get a living.

Owing to all these difficulties I have considered that it would be a good plan for you to have some of your men to cultivate some land and raise grain such as wheat, corn and potatoes and raise stock so that when the game fails or it becomes dangerous to go out after Buffalo you can have some food laid up from some other source upon which you can rely.

Now our people will show your men how to cultivate the land and assist them a little to get a start if you will have your men work as the whites do.[27] This you will find will be the best policy for you to pursue, and you will also want to build some houses to live in and settle down and have schools wherein your young men and women and children can learn to read and write so that they can communicate their ideas to one another as I do now to you.

Wash-e-kik think of these things and ask the Great Spirit to tell you if it is true and then act as the Great Spirit shall dictate.

VI

BRIGHAM YOUNG, SUPT. OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, TO

CHIEF WASHAKIE, DATED GREAT SALT LAKE CITY,

NOVEMBER 2, 1857

Wash-e-keek Head Chief of the Shoshones:

Our friend Ben. Simons[28] is about to make you a visit, and I am <p.254> pleased with the opportunity for sending you a few lines to let you know how I feel and how the Mormons feel.

Wash-e-keek, I love you and your people, for you have a good heart and your people are a good people and love peace. I and the Mormons love peace, and we wish to live in peace with our red brethren and do them all the good we can, and we want the Indians to be at peace with one another. Some of the whites in the United States are very angry at the Mormons because they wish to worship the Great Spirit in the way in which we believe he wants us to and have more than one wife, and they have sent some soldiers to this country[29] . . . . Now we do not want to fight them, if they will only go away and not try to abuse and kill us when we are trying to do right. But if they try to kill us we shall defend ourselves and our wives and children . . . .

Brother Beckstead and brother Davies are going to you with our friend Simons, and I wish you to treat them well.

I do not want you to fight the Americans and not to fight us for them, for we can take care of ourselves.

I am your brother

Brigham Young

When the mantle of territorial authority fell from Brigham Young to Jacob Forney following the Utah War, Washakie took the initiative and requested that the new Indian Superintendent send "a good white man, to instruct his people & farming implements, & his young men" would "do the work."[30] But as it turned out, neither the funds nor the Indians were forthcoming.[31] Despite this failure and the subsequent deterioration and disappearance of both federal and Mormon Indian farms between 1858 and 1865, Brigham Young kept the door open to prospective Indian farmers. Finally in 1874 one of the leading men among the Utah Shoshones named Egippetche[32] left his camp near Mendon in Cache Valley, <p.255> and "went into the lodge of Little Soldier and broached the subject of taking up some land somewhere and farm like white people. ''[33] This suggestion was accepted by Little Soldier and his people, so Egippetche traveled to Wellsville, Utah, where he asked Frank Gunnell, a well-known interpreter, to write Brigham Young concerning the proposal.[34] Young responded by calling George W. Hill to head a mission to the Indians to northern Utah in April, 1874. Hill was charged with the responsibility of locating the Indians in a "central gathering place where they can be taught the art of civilization, where they can be taught to cultivate the soil and become self-supporting."[35]

In 1881, after moving from five locations over a seven year period, three hundred Shoshones settled at the present site of Washakie, Utah, named after the Shoshone chief with whom Brigham Young had begun Indian farm negotiations twenty-seven years previous.[36] By 1886 the Indian settlement started "to assume the appearance of a prosperous little village."[37] A number of dwellings were constructed by the Indian farmers and the harvested crops enabled the Shoshones to both feed themselves and to trade with nearby Mormon settlements for other products. Until 1887 the Indian colony was holding its own in the Mormon community. Then on September 6, 1887, disaster began to strike the settlement. The mission store valued at $3000 was destroyed by fire. During the winter of 1887, the Indians lost $4000 worth of sheep and cattle and in 1889 a saw mill in which the Indians owned the principal stock was burned. These financial reverses were compounded by seven years loss of crops to grasshoppers between 1887 and 1896. Andrew Jenson recorded that in spite of these setbacks the Indians "stuck to their farm most manfully and throughout all their losses and difficulties they worked continuously hoping for better days."[38]

These events were not, however, without their effect on the settlement's population. Between 1881 and 1900, the colony of <p.256> reservationless Indians lost 113 discouraged associates, for the most part, to the Fort Hall and Wind River reservations in Idaho and Wyoming. In the next two decades to 1920, the population dropped from 187 to 114. This decrease of seventy-three was traced to the movement of Indian farmers to Utah towns where employment in vocations other than farming were sought. In the 1920's Washakie's total population increased by ten to 124 inhabitants. During the depression years, World War II and the post-war years to 1958, the colony's population fell to sixty. The biggest exodus of this twenty-eight year period took place after 1945. Few of the town's younger generation returned or remained at home long after the end of World War II. This trend continued until only ten Indians remained on the townsite at the beginning of 1967.[39]

Such a decrease in population over the past eighty-six years cannot be considered as an indication of total failure. Even though some of Washakie's inhabitants retreated to reservation life in the latter part of the Nineteenth Century, the majority of its citizens were absorbed into the affluent society of the post-1945 era. Such a movement was in keeping with Brigham Young's desire to see the Shoshones become a self-sufficient people. The genesis of this historical trend may be traced back to the contacts between Young and Washakie between 1854 and 1856, in which he introduced the topic of Indian farming to the Shoshone leader. What took place between 1854 and 1967 was unique to Mormon history if not to Western American history.

-------------------------------------

According to Victor H. Cohen's "James Bridger's Claims," Annals of Wyoming July, 1940, and J. Cecil Alter's James Bridger (Salt Lake City, Utah: Shepherd Book Co., 1924), the Mormon Green River Mission of 1853 was designed to undermine Bridger's influence in the region. That Brigham Young felt convinced that Bridger was inciting Indians against the Mormons cannot be questioned. Likewise it seems clear that Bndger and his associates did not appreciate Mormon social and economic contact with their Indian customers, and as a result did not encourage the native inhabitants to friendly relations with those they felt to be Mormon intruders. In light of these conditions, Cohen's and Alter's observation was quite correct. The Green River country was considered vital by Brigham Young to Mormon migration into Salt Lake Valley, and since peaceful relations with the Indians were essential to successful migration and the safety of Mormon settlers, Young undoubtedly felt that Bridger would have to go if he persisted in his unfriendly activities. Bridger apparently did not feel inclined to change his behavior so Young responded by issuing orders for Bridger's arrest on charges of inciting the Indians against Mormon emigrants as mentioned in the above letter.

In this feud between the Mormons and the mountainmen, Washakie's major concern seemed centered around securing a continued source of trade with the Mormons once Bridger had been displaced. That trade was forthcoming pleased Washakie, but the suggestion of becoming farmers was not appreciated by most Shoshone men even though Washakie seemed to at least entertain the idea.

--Wyoming State Historical Society, Annals of Wyoming,

Vol. 39 No. 2, Oct 1967, pp. 245-256.

Published here with permission of Rhett S. James,

17 March 2003.

To learn more about William Adams Hickman, click here.

To search the index to Brigham Young's Office files, click here.

To return to the Hickman Family index page, click here.